While there are some similarities between The Numinous Way, and what has come to be called Buddhism, there are also a number of fundamental differences, which differences make the two Ways quite different, and distinct, from each other.

In The Numinous Way there is only living numinously by, for example, valuing empathy, compassion, and honour, and cultivating, in a gentle manner, empathy and compassion, and having that inner balance, that harmony, that personal honour brings. Thus, there are no scriptures, no written or aural Canon, from some Buddha – from some human being who, having arrived, and been enlightened, has departed, leaving works to be reverentially recited and considered as the way to such enlightenment. In addition, there are no prescribed or recommended techniques – such as meditation – whereby it is said that personal understanding, development, or even such enlightenment can or could be obtained.

In The Numinous Way, while there is an appreciation and understanding of compassion, of the need to cease to cause and to alleviate suffering, there is also – unlike in Buddhism – and appreciation and understanding of the need for personal honour; for a Code of Honour, which sets numinous limits for our own personal behaviour and which also allows for and encourages self-defence, including, if necessary, the use of lethal force in such self-defence. Thus, in many ways, The Numinous Way is perhaps more human, more in harmony with our natural, human, character: that innate instinct for nobility, for fairness, that has evolved to become part of many (but, it seems, not all) human beings.

In addition, while honour limits our behaviour in certain ways, there is no asceticism, no rejection of the pleasures of life, of personal love; only an understanding of the need to not be excessive in such things; to not go beyond the bounds set by honour and evident in empathy, and thus not to cause suffering to others by, for example, excessive, uncontrolled, personal desire. For, in The Numinous Way, it is not human desire per se which is regarded as incorrect – as giving rise to samsara – but rather uncontrolled and dishonourable desire and personal behaviour, and a lack of empathy, which are incorrect, which are un-numinous, and thus which are de-evolutionary, and which contribute to or which cause or which can cause, suffering.

In The Numinous Way, while there is an appreciation and understanding of our own individuality, our self, as an illusion – a causal abstraction – this understanding and appreciation, unlike that of Buddhism, derives from a knowledge of our true nature as living beings, which is of us, as individuals (as a distinct living individual entity) being a nexion; a connexion, by and because of the acausal, to all other living beings not only on our planet, Earth, but also in the Cosmos. That is, our usual perception of ourselves as independent beings, possessed of what we term a self, is just a limited, causal, perception, and does not therefore describe our true nature, which is as part of the acausal and causal matrix of Life, of change, of evolution, which is the living Cosmos, and of a living Nature as part of that Cosmos: as the Cosmos presenced on this planet, Earth.

Expressed simply, the illusion of self, for The Numinous Way, is the practical manifestation of a lack of, or the loss of, empathy; the inability (or rather the loss of the ability) to translocate ourselves, our consciousness, into another living-being: an inability to become, if only for an instant, that other living-being. We lack this ability – or have lost this ability – because we have become trapped by or immersed in or allowed ourselves to be controlled by causal Time, by the separation of otherness.

The Numinous Way thus understands our real life as numinous; or rather, as possessing the nature, the character, of the numinous, of The Numen, with our causal, manufactured, abstractions – based on the linearity of causal Time, on a simple cause-and-effect – as obscuring, covering-up, severing, our connexion to the numinous and thus depriving us from being, or becoming, or presencing, the numinous in and through our own lives.

Living numinously is thus a re-discovery of our true nature, as living-beings existing in the Cosmos; a dis-covering; a removal of the causal abstractions, the illusions, that prevent us from knowing and appreciating our true nature, that prevent us or hinder us from knowing and appreciating, and ceasing to harm, all Life (often including ourselves, and other human beings); that prevent us or hinder us from knowing and appreciating, and ceasing to harm, Nature and the Cosmos itself. Living numinously is thus a re-discovery of how and why we are but part of Life itself; a removal of the causal illusion of us-and-them.

Living numinously is thus to discover, to achieve – to-be – the true purpose of our very existence, which is simply to participate, in a numinous manner, in our own change, our own evolution, and thus in the change, the evolution, of all Life, of Nature, and of the Cosmos itself. We thus become balanced, in harmony, with ourselves, with Life, with Nature and the Cosmos, and reconnect ourselves to the matrix, the acausal, The Unity, beyond and within us.

There is thus no Buddhist-type cycle of rebirth, in the realms of the causal, for those human beings who, in their causal lifetime, fail to understand causal abstractions for the Cosmic illusions that they are, and who thus fail to control their own desires, their own behaviour, in such a way that they no longer cause or contribute to the suffering of Life. There is only, for them, a failure to use their one mortal, causal, living to evolve to become part of the change, the evolution, of Life and of the Cosmos itself.

For, by living numinously, by becoming again and then expanding the nexion we are to all Life, to Nature, and to the Cosmos, what we are – our acausal essence presenced in and through our one causal existence – lives-on beyond our mortal, causal, death; not as some illusive, divisive, causal “individual”, but rather as the genesis of the evolution of Life; as the burgeoning, changing, awareness – the consciousness – of Life manifest in the numinous Cosmos itself. And a genesis, a burgeoning, a changing, an awareness, that – being acausal – cannot be adequately described by our limited causal words, our limited language, and our limited, causal, terminology. This living-on is not a pure cessation, not an extinguishing – not nirvana – but rather a simple, a numinous, change of “us”; an evolution to another state-of-noncausal-being, where a causal individuality has no meaning.

David Myatt

2010

In the now still warm air of an approaching English dusk, in middle of the month of April, I can hear the birdsong of a Thrush while I sit, outdoors, near a blossoming Cherry tree.

Nearby, the garden of an Inn – a Tavern, a Pub – is eerily silent because deserted. At this time of year there should be, there was for decades, the laughter, the bustling, the joy, of human beings.

Such human silence is, for me, unprecedented. Making me aware of how transient we as a terran species are on this planet we have named as Earth. Were we all to die – from some future pandemic or other – would Nature, presenced in such life as birds and trees, endure? Possibly. Probably.

Were we as a species to survive some future pandemic or other would we humans as a species learn from such a pathei-mathos and change our Nature-destroying, our unemphatic, ways? Are we capable of learning from such a pandemic as currently affects our human species?

Somehow, I doubt that we in our majority would – or even could – change our ways. Yet – and at least in my experience – there is a minority who would, who could, learn, and an even smaller minority, a pioneering few, who already if only intuitively foresaw such a Nature-born human calamity as now affects us, our societies. Foresaw, and changed their ways of life accordingly.

Perhaps, as I myself intuitively feel – listening as I now do in the burgeoning twilight to the birdsong of a Thrush near a blossoming Cherry tree – those pioneering few are or should be our future. For they are those who, with families or alone, mostly live, often in rural or wilderness areas, “off grid” and thus disconnected from modern means of communication and striving to be self-sufficient in terms of food and other essentials.

For such pioneering few there are no ideologies; no politics; no interfering desire – political or religious – to change what-is into what others passionately believe should-be. Instead, there is only their family or an individual desire to live in a more natural, a more intuitive, way with Nature, with the Cosmos. Only an awareness of how we – as individuals, as a family – are a nexion to Nature, to Earth, to the Cosmos and thus an awareness of how what we do or we do not do affects or can affect Nature, Earth, the Cosmos.

Is this understanding – this intuition – the essence of a modern paganism? Personally I believe that it is.

David Myatt

April 2020

Image Credit: Roscosmos / NTSOMZ

As referenced in my [2012] effusion Blue Reflected Starlight

“the Voyager 1 interplanetary spacecraft in 1990 (ce) transmitted an image of Earth from a distance of over four billion miles; the most distant image of Earth we human beings have ever seen. The Earth, our home, was a bluish dot; a mere Cosmic speck among the indefinity, visible only because of reflected starlight…”

NASA has now [February 2020] released an “updated version of the iconic Pale Blue Dot image taken by the Voyager 1 spacecraft [which] uses modern image-processing software and techniques” and which image I reproduce above. [1]

That we, our species, our planet, are merely “one speck in one galaxy in a vast Cosmos of billions upon billions of galaxies, and one speck that would most probably appear, to a non-terran, less interesting than the rings of Saturn, just visible from such a distance” [2] apparently still does not resonate with those who – elected by “democratic” means or who by other means rule over and and/or who create policy regarding us – are in positions of power and influence on planet Earth is both interesting and indicative.

Indicative, because – at least in my fallible judgement – it seems that they have no or little perception of, or are dismissive of, and certainly have no empathy regarding, our human history, over millennia: of the suffering, the deaths, the trauma, that abstractions, that ideology, that egoism, that dogma, that patriarchy, causes and has caused.

Interesting, because – at least in my fallible judgement – it seems that they have no or little perception of our Cosmic insignificance and thus have no or little perception of the balancing that a muliebral, an emphatic – a female physis and perspective, a presencing and understanding, and an understanding born of pathei-mathos – would necessitate and involve.

Are those masculous individuals currently in positions of power and influence in many modern terran governments likely or even amiable to such a muliebral physis and perspective; to such a balancing of the muliebral with the masculous; to such an Enantiodromia – to such a presencing and change?

I have to admit I do not know. If they and we are not amenable to such a change, and if we in our majority do not change, are we as a species then, in terms of Cosmic significance, irrelevant?

Perhaps.

David Myatt

February 2020

[1] https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=7593

[2] https://davidmyatt.wordpress.com/about/blue-reflected-starlight/

°°°

Concerning Humility, Tolerance, Islam, and Prejudice

The two texts below were both written in 2012 and both concern Islam and ethics. The first text is “from a reply sent, in November of 2012, to a personal correspondent living in America who enquired about my peregrinations among various religions [and] about why – as mentioned in previous correspondence – I still respected the Muslim way of life.”

The items in the second text “developed from – and in a many places summarize and/or quote from – replies I sent to various correspondents between February and November of 2012 and which correspondence concerned topics such as prejudice, my views concerning Islam and anti-Muslim groups, [and] the use of the terms culture and civilization.”

As I noted in the second text, both texts “present only my personal, fallible, opinion about such matters, and which opinion reflects the weltanschauung and the morality of my philosophy of pathei-mathos.”

I republish the texts since the problems and the attitudes described in them six years ago are still relevant – if not more relevant – now.

°°°

I. Humility and The Need for Tolerance

With Reference to Islam

Contents

° Prefatory Note

° Of Learning Humility and Tolerance

° Of Respect for Islam

° Terror and Al-Quran

° Of Islam and Violence

° Conclusion

Humility and The Need for Tolerance

(pdf)

Extract from the chapter entitled ‘Of Learning Humility and Tolerance’

“As someone who has lived an unusual and somewhat itinerant (but far from unique) life, I have a certain practical experience, over nearly fifty years, of various living religions and spiritual Ways of Life. An experience from which I have acquired the habit of respecting all those living religions and spiritual Ways: Christianity (especially Catholicism and monasticism); Buddhism; Islam; Taoism; Hinduism; Judaism; and the paganism manifest in an empathic appreciation of and a regard for Nature.

Due to this respect, there is a sadness within me because of the ignorance, intolerance, prejudice – and often the hatred – of the apparently increasing number of people, in modern Western societies, who disparage Islam, Muslims, and the Muslim way of life, and who thus seem to me to reflect and to display that hubris, that certitude-of-knowing, that lack of appreciation of the numinous, that at least in my fallible opinion and from my experience militates against the learning, the culture, the civility, that make us more than, or can make us more than, talking beings in thrall to their instincts who happen to walk upright.

My personal practical experience of, for example, Christianity, is of being raised a Catholic, and being a Catholic monk. Of Buddhism, of spending several years meditating and striving to follow the Noble Eightfold Path, including in a Buddhist monastery and with groups of Buddhists. Of Islam, of a decade living as a Muslim, performing daily Namaz (including attending Jummah Namaz in a Mosque), fasting in Ramadan, and travelling in Muslim lands. Of Taoism, of experience – in the Far East – a Taoist Martial Art and learning from a Taoist priest. Of Hinduism, of learning – in the Far East – from a Hindu lady and of over a year on my return to England continuing my learning and undertaking daily practice of Hatha Yoga according to the Haṭha Yoga Pradipika. Of paganism, of developing an empathic reverence and respect for Nature by time spent as a rural ‘gentleman of the road’, as a gardener, and by years doing outdoor manual labour on farms…..

Following a personal tragedy which suffused me with sadness and remorse and which – via pathei-mathos – ended my life-long desire for and enjoyment of practical Faustian peregrinations, there arose a years-long period of intense interior reflexion, and which reflexion included not only discovering and knowing the moral error of my immoral extremist pasts but also questions concerning the nature of faith, of God, and our desire, in times of personal grief and tragedy and remorse, and otherwise, to seek and often to need the guidance, the catharsis, of a religion or a spiritual Way.”

°°°

II. Concerning Islam, The West, Prejudice, and Islamophobia

Contents

° Prefatory Note

° Prejudice, Extremism, Islamophobia, and Culture

° Toward A Balanced View Of Islam and The West

° Concerning Islamophobia

Islam, The West, Prejudice, and Islamophobia

(pdf)

°°°

Several times, in the last decade or so, I have – when considering certain current events, and social change, and the activities, policies, and speeches, of certain politicians – often asked myself a particular question: What impression or what conclusions would a non-terran (a hypothetical visiting alien from another star-system) have of or draw from those events, such social change, and those politicians? And what, therefore, would be the conclusions that such a non-terran would make regarding our nature, our human character, as a species?

Which answers seemed to me to depend on what criteria – ethical, experiential, ontological, and otherwise – such a non-terran might employ. Would, for instance, the home-world of such a non-terran be a place of relative peace and prosperity which, having endured millennia of conflict and war, had evolved beyond conflict and war and had also ended poverty? Would, for instance, such a non-terran view matters dispassionately, having evolved such that they are always able to control – or have developed beyond – such strong personal emotions as now, as for all of our human history, so often still seem to overwhelm we humans leading us and having led us to be selfish, to lie, to cheat, to manipulate, to use violence – and sometimes kill – in order to fulfil a personal desire?

The criteria I now (post-2011) apply to this hypothetical scenario are those derived from my own experience, and from reflecting over several years upon that experience, which criteria are of course subjective, personal, and it is thus no coincidence that they now are reflected in my philosophy of pathei-mathos. Thus the ethics I assume such an interstellar space-faring sentient non-terran might adhere to are based on honour and the apprehension of suffering and hubris that empathy provides; just as the ontology derives from a numinous awareness of how causal and fallible and transient every sentient life is in respect of the vastness of the cosmos (spatially and in terms of aeons of causal time), with such ethics and ontology a natural consequence of such a culture whose genesis is that pathei-mathos – ancestral, individual, societal – that derives from millennia of suffering, conflict, war, poverty, corruption, and oppression.

Furthermore, my reflexion on the past fifty years of human space exploration leads me to further conclude that we as a species – and perhaps every sentient species – can only venture forth, en masse, to explore and colonize new worlds when certain social and political conditions exist: when we, when perhaps every sentient species, have matured sufficiently to be able to, as individuals, control ourselves (without any internal or external coercion deriving from laws or from some belief be such belief ideological, political, or religious) and thus when we use reason and empathy as our raison d’etre and not our emotions, our desires, our egoism or some -ism or some -ology or some faith that we accept or believe in or need. For despite the technology making such space exploration and colonization now feasible for us (if only currently within our solar system) we lack the political will, the social desire, the trans-national cooperation, the vision, to realize it even given that our own habitable planet is slowly undergoing a transformation for the worse wrought by ourselves. All we have – decades after the landings on the Moon – are a few individuals inhabiting and only for a while just one Earth-orbiting space station and a few small-scale, theorized, human landings on Mars a decade or more in the future. For instead of such a vision of a new frontier which frontier a multitude of families can settle and which can be the genesis of new cultures and new human societies, all we have had in the past fifty years is more of the same: regional wars and armed conflicts; invasions, violent coups and revolutions; violent protests, the killing and imprisonment and torture of protestors and dissenters; political propaganda for this political cause or that; exploitation of resources and of other humans; terrorism, murder, rape, theft, and greed.

How then would my hypothetical space-faring alien judge us as a species, and how would such a non-terran view such squabbles – political, social, ideological, religious, and be they violent or non-violent – and such poverty, inequality, and oppression, as still seem to so bedevil almost all societies currently existing on planet Earth?

In addition, how would we as individuals – and how would our governments – interact with, and treat, such an alien were such an alien, visiting Earth incognito, to be discovered? Would we treat such an alien with respect, with honour: as a non-threatening ambassador from another world? Would any current government on Earth willingly and openly and world-wide acknowledge the existence of such extra-terrestrial life and allow Earth ambassadors from any country, and scientists, and the media, full and open access to such an alien sentient being? I have my own personal intuition regarding answers to such questions.

But, remaining undiscovered, what would our visiting alien observer report regarding Earth and ourselves on their return to their own planet? Again, I have my own personal intuition regarding answers to such questions. Which answers could well be that we are an aggressive, still rather primitive and very violent, species best avoided until such time as we might outwardly demonstrate – through perhaps having numerous peaceful, cooperating, colonies on other worlds – that we have culturally and personally, in moral terms, advanced.

Which rather – to me at least – places certain current events, social change by -isms, by -ologies, through disruption and violence and via revolution, and the activities, policies, and speeches, of certain politicians, and armed conflicts, into what I intuit is a necessary cosmic, non-terran, perspective. Which perspective is of us as a species still evolving; as having the potential and now the means to further and to consciously, and as individuals, to so evolve.

Will we do this? And how? Again, my answer – fallible as it is, repeated by me as it hereby is, and born as it is from my own pathei-mathos – is that it could well begin with us as individuals consciously deciding to change through cultivating empathy and viewing ourselves and our world in the perspective of the cosmos. Which perspective is of our smallness, our fallibility, our mortality, and of our appreciation of the numinous and thus of the need to avoid the error of hubris; an error which we mortals, millennia following millennia, have always made and which even now – even with our ancestral world-wide culture of pathei-mathos – we still commit day after day, year after year, and century after century, enshrined as such hubris seems to be in so many politicians; in -isms and -ologies; in disruptive and violent social change and revolutions; in armed conflicts, and in our very physis as human individuals: an apparently unchanged physis which so motivates so many of us to still be egoistic, to lie, to cheat, to steal, to murder, to manipulate, to be violent, and to often be motived by avarice, pride, jealousy, and a selfish sexual desire.

As someone, over one and half-thousand years ago, wrote regarding human beings:

τοῖς δὲ ἀνοήτοις καὶ κακοῖς καὶ πονηροῖς καὶ φθονεροῖς καὶ πλεονέκταις καὶ φονεῦσι καὶ ἀσεβέσι πόρρωθέν εἰμι͵ τῷ τιμωρῷ ἐκχωρήσας δαίμονι͵ ὅστις τὴν ὀξύτητα τοῦ πυρὸς προσβάλλων θρώσκει αὐτὸν αἰσθητικῶς καὶ μᾶλλον ἐπὶ τὰς ἀνομίας αὐτὸν ὁπλίζει͵ ἵνα τύχῃ πλείονος τιμωρίας͵ καὶ οὐ παύεται ἐπ΄ ὀρέξεις ἀπλέ τους τὴν ἐπιθυμίαν ἔχων͵ ἀκορέστως σκοτομαχῶν͵ καὶ τοῦ τον βασανίζει͵ καὶ ἐπ΄ αὐτὸν πῦρ ἐπὶ τὸ πλεῖον αὐξάνει

“I keep myself distant from the unreasonable, the rotten, the malicious, the jealous, the greedy, the bloodthirsty, the hubriatic, instead, giving them up to the avenging daemon, who assigns to them the sharpness of fire, who visibly assails them, and who equips them for more lawlessness so that they happen upon even more vengeance. For they cannot control their excessive yearnings, are always in the darkness – which tests them – and thus increase that fire even more.” [1]

Which is basically the same understanding that Aeschylus revealed in his Oresteia trilogy many centuries before: the wisdom of pathei-mathos and the numinous pagan allegory of Μοῖραι τρίμορφοι μνήμονές τ᾽ Ἐρινύες [2], and which wisdom was also described by Milton over a millennia later by means of another allegory:

The infernal Serpent; he it was, whose guile,

Stirred up with envy and revenge, deceived

The mother of mankind.

David Myatt

2015

[1] Poemandres, 23. Corpus Hermeticum. Translated by DWM in Poemandres, A Translation and Commentary. 2014. ISBN 978-1495470684.

[2] Aeschylus (attributed), Prometheus Bound, 515-6

τίς οὖν ἀνάγκης ἐστὶν οἰακοστρόφος.

Μοῖραι τρίμορφοι μνήμονές τ᾽ Ἐρινύες

Who then compels to steer us?

Trimorphed Moirai with their ever-heedful Furies!

A Perplexing Failure To Understand

Being a slightly revised extract from a letter to a friend,

with some footnotes added post scriptum

°°°

A Perplexing Failure To Understand

(pdf)

Quite By Chance

Quite recently, and quite by chance, I found myself in an art gallery. The paintings so wyrdfully discovered rather resonated with me, causing me in subsequent days to learn more about the art, and life, of the artist: Shurooq Amin.

For her art seemed to make a connexion between the West and Islam; a quite personal connexion for me, given my somewhat outré past involving as it did a ‘reversion’ to Islam by a former fanatical exponent of Western culture who while travelling as a Muslim in the Muslim world had, albeit briefly, been engaged to a Muslimah in Egypt.

Thus was there for me, in that gallery at that time, another and quite numinous and quite fortuitous intimation of the importance of love, of the importance of the muliebral: beyond the rather stark, and often violent, most decidedly (in my view) misogynist, patriarchal, ethos that still seems to so dominate our world, East and West.

There was also a reminder, for me, of how Art can not only sometimes transcend human manufactured causal abstractions (such as nation, religion, and ethnicity) but can also be a rather acausal vector of that slow social, non-violent, evolutionary change whereby what is numinous, honourable, and so very human, can be presenced, to the benefit of us all.

DWM

2014

Image credit:

Shurooq Amin. The Dates Of Wrath. Mixed media on canvas mounted on wood. 2012.

Ayyam Gallery, Dubai

My weltanschauung – otherwise known as ‘the philosophy of pathei-mathos’ – is currently (2014-2015) outlined in the following four works, available both in printed format and as pdf files:

° David Myatt: The Numinous Way of Pathei-Mathos. 2013. 82 pages. ISBN 978-1484096642

pdf: https://davidmyatt.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/numinous-way-pathei-mathos-v7.pdf

° David Myatt: Religion, Empathy, and Pathei-Mathos. 2013. 60 pages. ISBN 978-1484097984

pdf: https://davidmyatt.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/myatt-religion-and-pathei-mathos.pdf

° David Myatt: One Vagabond In Exile From The Gods: Some Personal and Metaphysical Musings. 2014. 46 pages. ISBN 978-1502396105.

pdf: https://davidmyatt.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/one-vagabond-pathei-mathos.pdf

° David Myatt: Sarigthersa: Some Recent Essays. 50 pages. ISBN 978-1512137149

pdf: https://davidmyatt.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/dwmyatt-sarigthersa-v9.pdf

Also of interest may be:

° David Myatt: Understanding And Rejecting Extremism. 58 pages. ISBN 978-1484854266

pdf: https://davidmyatt.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/dwm-rejecting-extremism-v3.pdf

° J.R. Wright & R. Parker: The Mystic Philosophy of David Myatt. 56 pages. ISBN 978-1523930135

pdf: https://davidmyatt.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/myatt-philosophy-third-edition.pdf

The four essays provide an introduction to the philosophy of pathei-mathos.

Image credit: NGC 206, Hubble Space Telescope

Exordium

What I have previously described as the ‘philosophy of pathei-mathos’ and the ‘way of pathei-mathos’ is simply my own weltanschauung, a weltanschauung developed over some years as a result of my own pathei-mathos. Thus, and despite whatever veracity it may or may not possess, it is only the personal insight of one very fallible individual, a fallibility proven by my decades of selfishness and by my decades of reprehensible extremism both political and religious.

Furthermore, and according to my admittedly limited understanding and limited knowledge, this philosophy does not – in essence – express anything new. For I feel (and I use the word ‘feel’ intentionally) that I have only re-expressed what so many others, over millennia, have expressed as result of (i) their own pathei-mathos and/or (ii) their experiences/insights and/or (iii) their particular philosophical musings.

Indeed, the more I reflect upon my (perhaps pretentiously entitled) ‘philosophy of pathei-mathos’ the more I reminded of so many things, such as (i) what I intuitively (and possibly incorrectly) understood nearly half a century ago about Taoism when I lived in the Far East and was taught that ancient philosophy by someone who was also trying to instruct me in a particular Martial Art, and (ii) what I as a Catholic monk felt “singing Gregorian chant in choir and which singing often connected me to what JS Bach so often so well expressed by his music; that is, connected me to what – in essence – Christianity (the allegory of the life and crucifixion of Christ) and especially monasticism manifested: an intimation of some-thing sacred causing us to know beyond words what ‘the good’ really means, and which knowing touches us if only for an instant with a very personal humility and compassion”, and (iii) what I learnt from “my first few years as a Muslim, before I adhered to a harsh interpretation of Islam; a learning from being invited into the homes of Muslim families; sharing meals with them; praying with them; learning Muslim Adab; attending Namaz at my local Mosque, and feeling – understanding – what their faith meant to them and what Islam really meant, and manifested, as a practical way of living”, and (iv) of what I discovered from several years, as a teenager, at first in the Far East and then in England, of practising Hatha Yoga according to the Pradipika and Patanjali, and (v) of what I intuited regarding Buddhism from over a year of zazen (some in a zendo) and from months of discussions with Dom Aelred Graham who had lived in a Zen monastery in Japan, and (vi) what I so painfully, so personally, discovered via my own pathei-mathos.

As a weltanschauung derived from a personal pathei-mathos, my ‘philosophy/way of pathei-mathos’ is therefore subject to revision. Thus this essay summarising my weltanschauung includes a few (2013-2014) slight revisions – mentioned, or briefly described, in some of my more recent effusions – of what was expressed in previous works of mine such as The Numinous Way of Pathei-Mathos (ISBN 9781484096642) and Religion, Empathy, and Pathei-Mathos: Essays and Letters Regarding Spirituality, Humility, and A Learning From Grief (ISBN 9781484097984).

1. Ontology

The ontology is of causal and acausal being, with (i) causal being as revealed by phainómenon, by the five Aristotelian essentials and thus by science with its observations and theories and principle of ‘verifiability’, and (ii) acausal being as revealed by συμπάθεια – by the acausal knowing (of living beings) derived from faculty of empathy [1] – and thus of the distinction between the ‘time’ (the change) of living-beings and the ‘time’ described via the measurement of the observed or the assumed/posited/predicted movement of ‘things’ [2].

2. Epistemology

a. The primacy of pathei-mathos: of a personal pathei-mathos being one of the primary means whereby we can come to know the true φύσις (physis) of Being, of beings, and of our own being; a knowing beyond ‘abstractions’, beyond the concealment implicit in manufactured opposites, by ipseity (the separation-of-otherness), and by denotatum.

b. Adding the ‘acausal knowing’ revealed by the (muliebral) faculty of empathy to the conventional, and causal (and somewhat masculous), knowing of science and logical philosophical speculation, with the proviso that what such ‘acausal knowing’ reveals is (i) of φύσις, the relation between beings, and between beings and Being, and thus of ‘the separation-of-otherness’, and (ii) the personal and numinous nature of such knowing in the immediacy-of-the-moment, and which empathic knowing thus cannot be abstracted out from that ‘living moment’ via denotatum: by (words written or spoken), or be named or described or expressed (become fixed or ‘known’) by any dogma or any -ism or any -ology, be such -isms or -ologies conventionally understood as political, religious, ideological, or social.

c. Describing a human, and world-wide and ancestral, ‘culture of pathei-mathos’ [3], and which culture of pathei-mathos could form part of Studia Humanitatis and thus of that education that enables we human beings to better understand our own φύσις [4].

3. Ethics

a. Of personal honour – which presences the virtues of fairness, tolerance, compassion, humility, and εὐταξία – as (i) a natural intuitive (wordless) expression of the numinous (‘the good’, δίκη, συμπάθεια) and (ii) of both what the culture of pathei-mathos and the acausal-knowing of empathy reveal we should do (or incline us toward doing) in the immediacy of the personal moment when personally confronted by what is unfair, unjust, and extreme [5].

b. Of how such honour – by its and our φύσις – is and can only ever be personal, and thus cannot be extracted out from the ‘living moment’ and our participation in the moment; for it only through such things as a personal study of the culture of pathei-mathos and the development of the faculty of empathy that a person who does not naturally possess the instinct for δίκη can develope what is essentially ‘the human faculty of honour’, and which faculty is often appreciated and/or discovered via our own personal pathei-mathos.

4. One fallible, personal, answer regarding the question of human existence

Of understanding ourselves in that supra-personal, and cosmic, perspective that empathy, honour, and pathei-mathos – and thus an awareness of the numinous and of the acausal – incline us toward, and which understanding is: (i) of ourselves as a finite, fragile, causal, viatorial, microcosmic, affective effluvium [6] of Life (ψυχή) and thus connected to all other living beings, human, terran, and non-terran, and (ii) of there being no supra-personal goal to strive toward because all supra-personal goals are and have been just posited – assumed, abstracted – goals derived from the illusion of ipseity, and/or from some illusive abstraction, and/or from that misapprehension of our φύσις that arises from a lack of empathy, honour, and pathei-mathos.

For a living in the moment, in a balanced – an empathic, honourable – way, presences our φύσις as conscious beings capable of discovering and understanding and living in accord with our connexion to other life; which understanding inclines us to avoid the hubris that causes or contributes to the suffering of other life, with such avoidance a personal choice not because it is conceived as a path toward some posited thing or goal – such as nirvana or Jannah or Heaven or after-life – and not because we might be rewarded by God, by the gods, or by some supra-personal divinity, but rather because it manifests the reality, the truth – the meaning – of our being. The truth that (i) we are (or we are capable of being) one affective consciously-aware connexion to other life possessed of the capacity to cause suffering/harm or not to cause suffering/harm, and (ii) we as an individual are but one viator manifesting the change – the being, the φύσις – of the Cosmos/mundus toward (a) a conscious awareness (an aiding of ψυχή), or (b) stasis, or (c) as a contributor toward a decline, toward a loss of ψυχή.

Thus, there is a perceiveration of our φύσις; of us as – and not separate from – the Cosmos: a knowledge of ourselves as the Cosmos presenced (embodied, incarnated) in a particular time and place and in a particular way. Of how we affect or can affect other effluvia, other livings beings, in either a harmful or a non-harming manner. An apprehension, that is, of the genesis of suffering and of how we, as human beings possessed of the faculties of reason, of honour, and of empathy, have the ability to cease to harm other living beings. Furthermore, and in respect of the genesis of suffering, this particular perceiveration provides an important insight about ourselves, as conscious beings; which insight is of the division we mistakenly but understandably make, and have made, consciously or unconsciously, between our own being – our ipseity – and that of other living beings, whereas such a distinction is only an illusion – appearance, hubris, a manufactured abstraction – and the genesis of such suffering as we have inflicted for millennia, and continue to inflict, on other life, human and otherwise.

David Myatt

September 2014

Notes

[1] Refer to: (i) The Way of Pathei-Mathos – A Philosophical Compendiary (pdf, Third Edition, 2012), and (ii) Towards Understanding The Acausal, 2011.

[2] Refer to Time And The Separation Of Otherness – Part One, 2012.

[3] The culture of pathei-mathos is the accumulated pathei-mathos of individuals, world-wide, over thousands of years, as (i) described in memoirs, aural stories, and historical accounts; as (ii) have inspired particular works of literature or poetry or drama; as (iii) expressed via non-verbal mediums such as music and Art, and as (iv) manifest in more recent times by ‘art-forms’ such as films and documentaries.

[4] Refer to Education and The Culture of Pathei-Mathos, 2014.

[5] By ‘extreme’ is meant ‘to be harsh’, unbalanced, intolerant, prejudiced, hubriatic.

[6] As mentioned elsewhere, I now prefer the term effluvium, in preference to emanation, in order to try and avoid any potential misunderstanding. For although I have previously used the term ’emanation’ in my philosophy of pathei-mathos as a synonym of effluvium, ’emanation’ is often understood in the sense of some-thing proceeding from, or having, a source; as for example in theological use where the source is considered to be God or some aspect of a divinity. Effluvium, however, has (so far as I am aware) no theological connotations and accurately describes the perceiveration: a flowing of what-is, sans the assumption of a primal cause, and sans a division or a distinction between ‘us’ – we mortals – and some-thing else, be this some-thing else God, a divinity, or some assumed, ideated, cause, essence, origin, or form.

One of the many subjects that I have pondered upon in the last few years is the role of education and whether a learning of our thousands of years old human culture of pathei-mathos – understood and appreciated as a distinct culture [1], and thence as an academic subject – could possibly aid us, as a species, to change; aid us to become more honourable, more compassionate, less egoistical, less violent, as individuals, and thus aid us to possibly avoid in our own lives those hubriatic errors, and causing the suffering, that the culture of pathei-mathos reveals are not only unethical but also which we humans make and cause and have made and caused again and again and again. That is, can a knowledge and appreciation of this culture, perhaps learnt individually and/or in institutions such as schools and colleges, provide with us with that empathic, supra-personal, perspective which I personally – as a result of my own learning and experiences – am inclined to feel could change, evolve, us not only as individuals but as a species?

Studia Humanitatis

For thousands of years – from the classical world to the Renaissance to fairly recent times – Studia Humanitatis (an appreciation and understanding of our φύσις as human beings) was considered to be the basis of a good, a sound, education.

Thus, for Cicero, Studia Humanitatis implied forming and shaping the manners, the character, and the knowledge, of young people through them acquiring an understanding of subjects such as philosophy, geometry, rhetoric, music, and litterarum cognitio (literary culture). This was because the classical weltanschauung was a paganus one: an apprehension of the complete unity (a cosmic order, κόσμος, mundus) beyond the apparent parts of that unity, together with the perceiveration that we mortals – albeit a mere and fallible part of the unity – have been gifted with our existence so that we may perceive and understand this unity, and, having so perceived, may ourselves seek to be whole, and thus become as balanced (perfectus) [2], as harmonious, as the unity itself:

Neque enim est quicquam aliud praeter mundum quoi nihil absit quodque undique aptum atque perfectum expletumque sit omnibus suis numeris et partibus […] ipse autem homo ortus est ad mundum contemplandum et imitandum – nullo modo perfectus, sed est quaedam particula perfecti. [3]

Furthermore, this paganus natural balance implied an acceptance by the individual of certain communal responsibilities and duties; of such responsibilities and duties, and their cultivation, as a natural and necessary part of our existence as mortals.

In the Christian societies of Renaissance Europe, Studia Humanitatis became more limited, to subjects such as history, moral philosophy, poetry, certain classical authors, and Christian writers such as Augustine and Jerome, with the general intent being a self improvement with the important proviso that this concentration on the advancement of the individual to ‘noble living’ by means of ‘noble examples’ (classical and Christian) should not conflict with the Christian weltanschauung [4] and its perceiveration of obedience to whatever interpretation of Christian faith and eschatology the individual favoured or believed in. In more recent times, Studia Humanitatis has become the academic study of ‘the liberal arts’, the ‘humanities’, often as a means to equip an individual with certain personal skills – such as the ability to communicate effectively and to rationally analyse problems – which might be professionally useful in later life.

However, the culture of pathei-mathos provides an addition to the aforementioned Studia Humanitatis, and an addition where the focus is not on a particular weltanschauung (paganus, Christian, liberal, or humanist) but rather on our shared pathei-mathos: on what we and others have learnt, and can learn, about our human φύσις from experience of grief, suffering, trauma, injustice. For it is such personal learning from experience, or the records of or the influence of the experiences of others, which is not only the essence of much of what we, and others for thousands of years, have appreciated and learned from some of the individual subjects or fields of learning that formed the basis for the aforementioned Studia Humanitatis – history, litterarum cognitio, and music, for example – but also what, at least in my view, provides us with perhaps the deepest, but most certainly with the most poignant, insight into our φύσις as human beings.

Thus considered as an individual subject or field of learning, academic or otherwise, the culture of pathei-mathos would most certainly help to form and shape the manners, the character, the knowledge, of young people, for it has the potential to provide us with a perception and an understanding of the supra-personal unity – the mundus – of which we are a mortal part, and thus perhaps can aid us to become as inwardly balanced, as harmonious, as the unity beyond and encompassing us, bringing as such a perception, understanding, and balance, does that appreciation and empathic intuition of others which is compassion and aiding as such compassion does the cessation of the suffering that an unbalanced – a hubriatic, egoistical – human φύσις causes and has caused for so many millennia.

Can we therefore, as described in the Pœmandres tractate,

hasten through the harmonious structure, offering up, in the first realm, that vigour which grows and which fades, and – in the second one – those dishonourable machinations, no longer functioning. In the third, that eagerness which deceives, no longer functioning; in the fourth, the arrogance of command, no longer insatiable; in the fifth, profane insolence and reckless haste; in the sixth, the bad inclinations occasioned by riches, no longer functioning; and in the seventh realm, the lies that lie in wait. [5]

For is not to so journey toward the unity “the noble goal of those who seek to acquire knowledge?”

But if we cannot make that or a similar personal journey; if we do not or cannot learn from our human culture of pathei-mathos, from the many thousands of years of such suffering as that culture documents and presents and remembers; if we no longer concern ourselves with de studiis humanitatis ac litterarum, then do we as a sentient species deserve to survive? For if we cannot so learn, cannot so change, cannot so educate ourselves, or are not so educated in such subjects, then it seems to me we may never be able to escape to the freedom and the natural evolution, the diversity, that await among the star-systems of our Galaxy. For what awaits us if we, the unlearned, stay unchanged, are only repetitions of the periodicity of human-caused suffering until such time as we exhaust, lay waste, make extinct, our cultures, our planet, and finally ourselves. And no other sentient life, elsewhere in the Cosmos, would mourn our demise.

David Myatt

May 2014

From a letter sent to a personal correspondent. Some footnotes have been added, post scriptum, in an effort to elucidate some parts of the text and provide appropriate references.

Notes

[1] I define the culture of pathei-mathos as the accumulated pathei-mathos of individuals, world-wide, over thousands of years, as (i) described in memoirs, aural stories, and historical accounts; as (ii) have inspired particular works of literature or poetry or drama; as (iii) expressed via non-verbal mediums such as music and Art, and as (iv) manifest in more recent times by ‘art-forms’ such as films and documentaries.

The culture of pathei-mathos thus includes not only traditional accounts of, or accounts inspired by, personal pathei-mathos, old and modern – such as the With The Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa by Eugene Sledge, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, and the poetry of people as diverse as Sappho and Sylvia Plath – but also works or art-forms inspired by such pathei-mathos, whether personal or otherwise, and whether factually presented or fictionalized. Hence films such as Monsieur Lazhar and Etz Limon may poignantly express something about our φύσις as human beings and thus form part of the culture of pathei-mathos.

[2] A pedantic aside: it is my considered opinion that the English term ‘balanced’ (a natural completeness, a natural equilibrium) is often a better translation of the classical Latin perfectus than the commonly accepted translation of ‘perfect’, given what the English word ‘perfect’ now imputes (as in, for example, ‘cannot be improved upon’), and given the association of the word ‘perfect’ with Christian theology and exegesis (as, for example, in suggesting a moral perfection).

[3] M. Tullius Cicero, De Natura Deorum, Liber Secundus, xiii, xiv, 37

[4] q.v. Bruni d’Arezzo, De Studiis et Litteris. Leipzig, 1496.

[5] My translation of the Greek text. From Mercvrii Trismegisti Pymander de potestate et sapientia dei – A Translation and Commentary. 2013. A pdf version is available here – pymander-hermetica-pdf

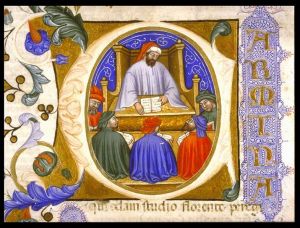

Image credit: Glasgow University library: MS Hunter 374 fol.4r

Boethius Consolation of Philosophy

Unde non iniuria tragicus exclamat:

῏Ω δόξα, δόξα, μυρίοισι δὴ βροτῶν

οὐδὲν γεγῶσι βίοτον ὤγκωσας μέγαν

For most of my life – and to paraphrase what someone once wrote – I have been a selfish being, prideful and conceited, and would still be so were it not for the suicide of a woman I loved. For not only did I often use words to deceive, to manipulate, to charm, but I also deluded myself, since I really, arrogantly, believed that I was not a bad person and could always find some excuse (for myself and for others) to explain away what in objective terms amounted to selfish behaviour, just as – by adhering to the idea of patriotism, or to some political ideology or to some harsh interpretation of some religion – I had a sense of identity, found a purpose, to vivify, excite, entice, and provide me with excuses to be deceitful, manipulative, prideful, conceited, and violent; that is, with a raison d’être for being who and what I was by instinct, by nature: a reprehensible arrogant opinionated person who generally placed his own needs, or the apparent demands of some ideology or some dogma, before the feelings – before the happiness – of others.

But am I, as one correspondent once wrote to me almost two years ago, being too hard on myself? I do not feel I am, for when she asked why I cannot “show the same compassion and forgiveness to your younger self that you could show to someone else who had made mistakes earlier in life,” I (somewhat pompously) replied: “Because that would not – probably could never – be a neutral point of view, for there are memories, a remembering, of deeds done and a knowing of their suffering-causing effects on others. It is not for me to seek – to try – to forget; not for me to offer myself expiation. For I sense that to do so would be hubris and thus continue the periodicity of suffering.”

For unfortunately I – with such a prideful, conceited, selfish nature – am no exception; just as the type I represented has been no exception throughout our history as sentient beings. Indeed, my particular type is perhaps more reprehensible than the brutish barbarian archetype that many will associate with those humans who survive by natural, selfish, instinct alone. For not only did I live in the prosperous West (or in colonial outposts of the West) but I had the veneer of culture – the benefits of a classical education, a happy childhood – and so could converse (although often only in my then opinionated manner) about such things as music, art, literature, poetry, and history. In many ways, therefore, I was the archetypal paradoxical National-Socialist: a throwback, perhaps, to those educated, cultured, Germans who could and who did support and then fight for the demagogue Hitler and who, in his name, could and did commit, or ignore or make excuses for, nazi atrocities.

Most important of all, it was not something I did, not something I read or studied or thought, and not some sudden ‘revelation’ or epiphany related to some religion or to some belief, that fundamentally changed me. Instead, it was something entirely independent of me; something unexpected, traumatic, outside of my control and my experience, involving someone I personally knew, and indeed whom I loved, or as much as I – the selfish survivor – was capable of love.

For would I, without personally suffering that personal trauma, have changed? Would I, without such a personal trauma, have been even capable of discovering and then accepting the truth about myself and the truth about the harsh interpretation of a Way of Life I then adhered to and the truth about an ideology I had previously adhered to and believed in for some three decades? No, I would not. For I was too arrogant; too enamoured with my certitude-of-knowing; far too selfish, and far too vitalized by some ideology or by the dogmatism of a particularly harsh interpretation of some faith. It is little wonder, therefore, that since that personal trauma I have pondered, over and over again, on certain philosophical, ethical, metaphysical, questions; seeking to find at least some answers, however fallible.

Perhaps most of all – and especially in the past year – I have thought about the nature of suffering; its causes, genesis, and its possible alleviation through or because of such things as education, pathei-mathos, and a knowing of or assumptions concerning whether our sentient life has a meaning, and if so what this meaning might be.

In respect of causes, there is, for example, the question of good individual character and bad individual character, and how we can distinguish – or even if we can distinguish and know – the good from the bad. There is, in respect of possibly in some way alleviating or not causing suffering, the question of culture; and the question of whether culture can fundamentally change us in character – as a species gifted with the faculties of speech and reason – in sufficient numbers world-wide so that we cease the cause the suffering we inflict and have for millennia inflicted on our own kind and on the other life with which we share this planet. Which leads to questions regarding our future if we cannot so change ourselves; and to questions concerning laws and education and authority. And thence, of course, to the raison d’être of “the body politic as organized for supreme civil rule and government.”

In respect of suffering, one of the questions we might ask is how much suffering have we humans, in the past year and around the world, inflicted on our own kind? How many murdered, how many injured and maimed? How many humiliated, subjected to violence? How many women raped, beaten, injured? How many human beings have been tortured or suffered injustice? How many human beings have been manipulated, deceived, exploited, lied to, or had possessions stolen? How many have died of preventable hunger or curable disease? How many have endured or been forced to endure poverty? How many homeless, how many made refugees? How much more of Nature have we destroyed or exploited in the past year in our apparent insatiable need for, or in greedful desire to exploit, Earth’s resources, biological, physical, or otherwise?

Furthermore, how much of the suffering inflicted on our own kind is personal, the consequence of some uncontrolled or uncontrollable personal emotion, desire, or instinct? And how much inflicted is due to some excuse – some idea or abstraction – we as individuals use, have used, or might use: excuses such as some war, some armed conflict, some ideology, some political extremism, some interpretation of some religion? How much inflicted because of ‘obeying some higher authority’ or some chain of command? How much because ‘we’ had a certainty-of-knowing that we (or our cause, or our State, or our nation, or our faith, or our ideology, or our organization, or our government) were right and that ‘they’ (the others) were wrong and/or they ‘deserved’ it and/or it needed to or had to be done in the interest of some idea or some abstraction, such as ‘our’ security, ‘our’ (or even ‘their’) freedom or happiness, or because our laws made it acceptable?

We might go on to ask whether the personal suffering caused is greater this year than last. Whether the suffering caused by or on behalf of some excuse – some idea or abstraction – is greater this year than last. Greater than a decade ago? Less than that caused a century ago? A millennia ago? And would such a crude measure of suffering – were it even possible to ascertain the figures – really be an indicator of whether or not we as a species have changed? And have modern States and nations – with their armies, their governments, their schools, their universities, their culture, their forces and institutions and traditions of law and order – really made a difference or just caused more suffering?

But do – or should – these questions matter? Asking such questions returns me to the question of whether our sentient life has a meaning, and if so what this might be, and thence to questions concerning good and bad personal character, and thus to what it is or might be for us, as individuals, wise to seek and wise to avoid.

Based on my limited knowledge, and according to my certainly fallible understanding, it seems to me that interpretations of our mortal life are often predicated on a specific cause or origin. For a religious interpretation, this is often God, or Allah, or the gods, or an inscrutable mechanism such as karma, with – it is claimed – such a ‘first cause’ revealing to us the truth concerning our existence. In the case of God, or Allah, it is that we were created and placed on this Earth as a way to attain immortality (Heaven, Jannah), and, in the case of karma, it is nirvana [the wordless nibbana], attainable for example by the Noble Eightfold Way as explained by Siddhartha Gautama.

For many non-religious, but material, interpretations the specific cause is our own perception, or consciousness, or feelings; with the truth concerning our existence then being, for example, (i) that it is only we ourselves who create or can create or who should create a meaning or give a value to our existence; or (ii) that what is most valuable is our personal happiness and/or our freedom, a freedom from such things as suffering, fear, and oppression.

For many non-religious, but spiritual, interpretations the specific cause is our ‘loss of balance or our loss of harmony’ with Nature and/or with existence itself; with the truth concerning our existence then being to regain that natural balance, that harmony (which it is assumed most of us are born with); and regain by, for example, a virtuous living respectful of others, or by acquiring – and living according to – reason, or by moderation in all things, or by trying to avoid causing suffering in other living beings, human and otherwise by, for example, embracing ‘love’ and ‘peace’ and thus being loving and non-violent.

Personally, and as a result of my pathei-mathos and several years reflecting on various philosophical questions, I favour a non-religious, but still rather spiritual, interpretation where there is no assumed loss of some-thing but rather where there is only that type of apprehension – that individual perceiveration – which provides us as individuals with an often wordless but always numinous awareness of our own, individual, life in a cosmic (supra-personal) context. There is then no yearning or necessity to attain or regain some-thing because there is no-thing to attain or regain, and thus no techniques, no practices, no special manner of living, no journey, no ἄνοδος, from ‘here’ to ‘there’. For such a yearning or assumed necessity – however expressed, such as in terms of Heaven, Jannah, nirvana, harmony, immortality, peace, and so on – implies or manifests or can manifest a separation of ‘us’ from ‘them’, manifest for example in ‘those who know’ (or who believe or who assert they know) and those ‘others’ who as yet do not know, giving rise to a certain hierarchy; of those who believe or who assert they can teach or reveal this knowing – and the means to acquire or attain the assumed goal or regain what has been lost – and of those who are, or who can be, or who should be, taught or ‘enlightened’.

Interestingly, this perceiveration of ourselves in a cosmic context is acausal: there are no hierarchies, no posited primal cause, no-thing lost or to be acquired (or reacquired), and no-thing that needs to be (or which can be) described to others in any emotive manner or by means of some abstraction or some idea/form. There is only a particular and a personal and quite gentle awareness: of ourselves as a microcosmic, viatorial, fleeting, effluvium [1] of the Cosmos, but an effluvium which is not only alive but which has a faculty enabling us (the effluvia presenced as a human being) to be perceptful of this, perceptful of how were are connected to other effluvia and thus perceptful of how what we do or do not do can and does affect other effluvia and thus the Cosmos itself. For the perceiveration is of our φύσις, of us as – and not separate from – the Cosmos; of living beings as the Cosmos presenced (embodied, incarnated) in a particular time and place and in a particular way; of how we affect or can affect other effluvia, other livings beings, in either a harmful or non-harming way. An apprehension, that is, of the genesis of suffering and of how we, as human beings possessed of the faculties of reason and of empathy, have the ability to cease to harm other human beings.

In respect of the genesis of suffering, this particular perceiveration provides an important insight about ourselves, as conscious beings; which insight is of the division we make, and have made, consciously or unconsciously, between our own being – our selfhood, ipseity – and that of other living beings, and of that personal ipseity having or possibly having some significance beyond our own finite mortal life either in terms of some-thing (such as a soul) having an opportunity to live on elsewhere (Heaven, Jannah, for example) or as our mortal individual deeds having had a long-lasting causal effect on others.

While it can be argued, and has been argued, that this division exists – is a re-presentation of the current (and past) reality of our existence as conscious, thinking, beings – what is important is not whether it does exist or whether it may be an illusion, but rather (i) that the perceiveration of ‘the acausal’ is an intimation of what is beyond the current (and the past) personal ipseity (real or assumed), and (ii) that it is such personal ipseity (real or assumed) which is the genesis of suffering, and (iii) that this understanding of the genesis of suffering affords us an opportunity to consciously change ourselves, from our current (and the past) real/assumed personal ipseity, and thus, so being changed, no longer cause or contribute to suffering.

How then can we so consciously change? By cultivating and manifesting in our own lives the personal virtues of empathy, compassion, and humility. For it is these virtues which, by removing us from our ipseity – by making us aware of our affective connexion to other life – make us aware of suffering and its causes and prevent us, personally, from causing suffering to other living beings, human and otherwise.

Thus, my personal answer to the question of good and bad personal character is that a person of good personal character is someone who is or who seeks to be compassionate, who has a numinous sympatheia for other living beings, and who is modest and self-effacing. And it is wise to avoid causing or contributing to suffering not because such avoidance is a path toward nirvana (or some other posited thing), and not because we might be rewarded by God, by the gods, or by some divinity, but rather because it manifests the reality, the truth – the meaning – of our being, and which truth is some consolation for this particular viator.

David Myatt

May 2014

In Loving Memory of Frances, who died May 29th 2006

Note

The title of this essay was inspired by a passage in the 1517 translation by William Atkynson of a work by Thomas à Kempis, a translation published as A Full Deuout and Gostely Treatyse of the Imytacyon and Folowynge the Blessed Lyfe of Our Moste Mercyfull Sauyour Cryste.